In this week you will:

- learn different optimization methods such as (Stochastic) Gradient Descent, Momentum, RMSProp and Adam.

- Use random minibatches to accelerate the convergence and improve the optimization.

- Know the benefits of learning rate decay and apply it to your optimization.

Gradient Descent

Recall the update rule for gradient descent:

for \(l\) in \(L\):

\[W^{[l]} = W^{[l]} - \alpha \text{ } dW^{[l]} \tag{1}\] \[b^{[l]} = b^{[l]} - \alpha \text{ } db^{[l]} \tag{2}\]Where:

\(W: \text{ Weights} \)

\( b: \text{ biases} \)

\( \alpha: \text{ learning rate} \)

\( l: \text{ layer number} \)

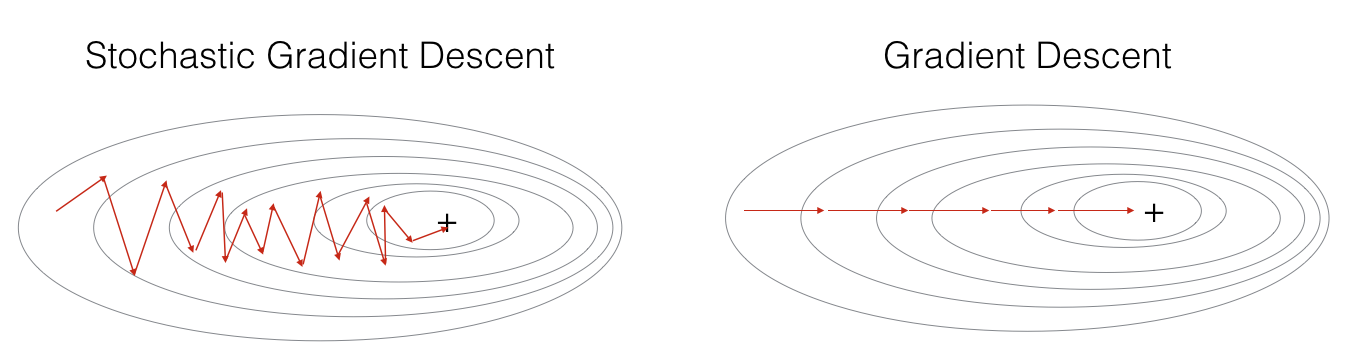

Batch Gradient Descent

- We update parameter every m example.

- We take gradient steps with respect to all \(m\) examples on each step.

- Equivalent to mini-batch gradient descent but with mini-batch size of \(m\).

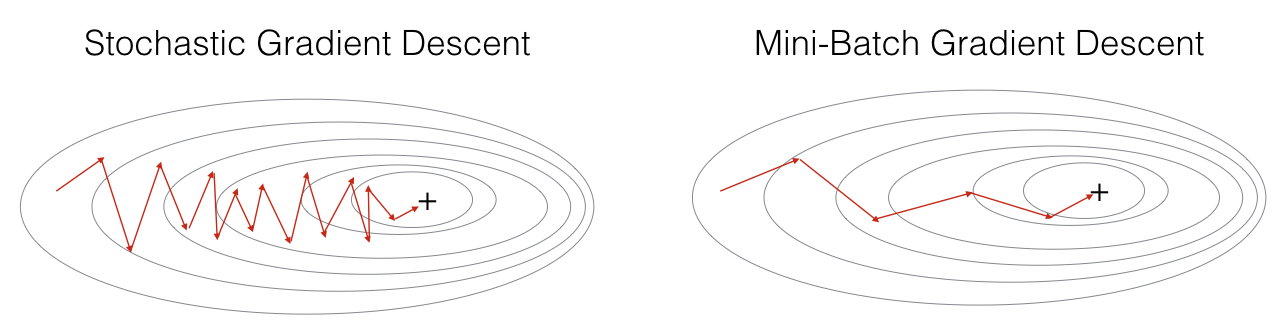

Stochastic Gradient Descent

- We compute gradients on one training example.

- We update parameter every 1 example.

- Equivalent to mini-batch gradient descent but with mini-batch size of \(1\).

Mini-batch Gradient Descent

- we update parameter every subset of examples.

- mini-batch size is between \(1\) and \(m\).

- It’s better to choose the mini-batch size to be powers of 2.

- it’s build in two steps:

- Shuffling (To ensures that examples will be split randomly into different mini-batches).

- Partition

- Note that the number of training examples is not always divisible by mini_batch_size.

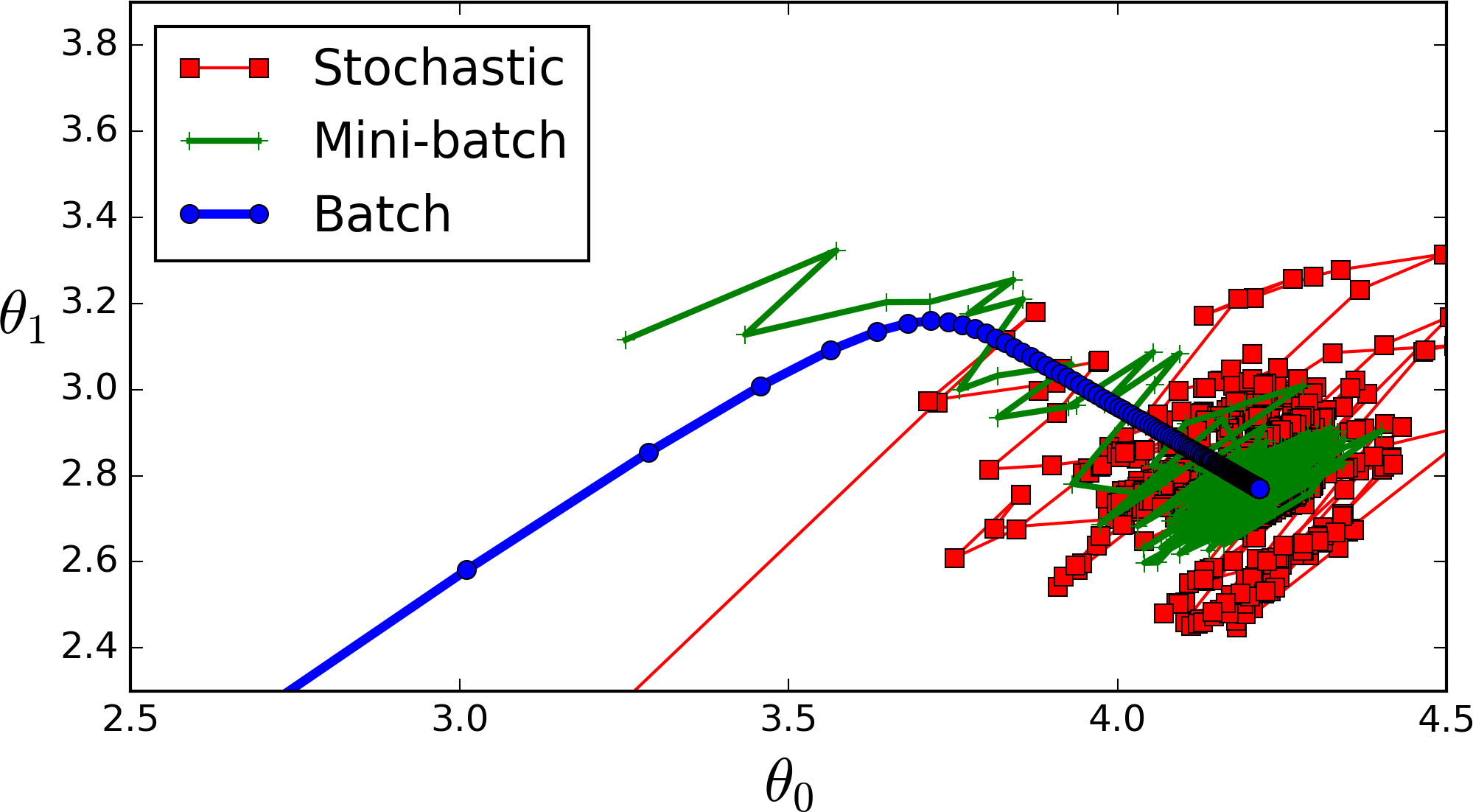

Extra: Here is a comparison that combines the three algorithms.

Gradient descent with momentum

- Using momentum can reduce the oscilation of mini-batch path toward convergence.

- Based on exponentially weigted averages.

- Takes into account past gradients to smooth out the update path.

- Direction of previous gradients is stored in \(v\) which can be seen as the velocity of a ball rolling down the pow.

- Velocities are initialized with zeros, that’s why the algorithms takes some time (few iterations) to warm up.

- If \(\beta = 0 \) this will be the standard gradient descent.

- beta is another hyperparamter that could be tuned, to reduce the value of cost funcion \(J\).

- The larger beta is the smother the path toward converence get, because more past gradient is taken into account.

- Common values for \(\beta\) is between 0.8 and 0.999.

- 0.9 is often resonable choice if you don’t want to tune it.

- Momentum can be applied with batch gradient descent, mini-batch gradient descent or stochastic gradient descent.

Momentum update rule:

for \(l\) in \(L\):

\[\begin{cases} v_{dW^{[l]}} = \beta v_{dW^{[l]}} + (1 - \beta) dW^{[l]} \\ W^{[l]} = W^{[l]} - \alpha v_{dW^{[l]}} \end{cases}\tag{3}\] \[\begin{cases} v_{db^{[l]}} = \beta v_{db^{[l]}} + (1 - \beta) db^{[l]} \\ b^{[l]} = b^{[l]} - \alpha v_{db^{[l]}} \end{cases}\tag{4}\]Where:

\(\beta: \text{ momentum} \)

\(v: \text{ velocity} \)

RMSProp

Surprisingly RMSProp was not introduced in some reasearch paper but a course in Coursera by Geoff Hinton!

\[s_{dW^{[l]}} = \beta_2 s_{dW^{[l]}} + (1 - \beta_2)(dW^{[l]})^2\] \[W^{[l]} = W^{[l]} - \alpha \frac{dW^{[l]}}{\sqrt{s_{dW^{[l]}} + \varepsilon}}\]- \(\varepsilon\) is to avoid the division by zero.

- RMSProp stands for root mean squared prop.

Adam optimization algorithm

- Combines the advantages of RMSProb and Momentum

- We have two variables \(v,s\) that keeps track of the past information.

How does it work?

Simply it:

- Calculates an exponentially weighted average of past gradients, and stores it in variables v (before bias correction) and vcorrected (with bias correction).

- Calculates an exponentially weighted average of the squares of the past gradients, and stores it in variables s (before bias correction) and scorrected (with bias correction).

- Updates parameters in a direction based on combining information from “1” and “2”.

The update rule is:

\(\text{for } l = 1, …, L:\)

\[\begin{cases} v_{dW^{[l]}} = \beta_1 v_{dW^{[l]}} + (1 - \beta_1) \frac{\partial \mathcal{J} }{ \partial W^{[l]} } \\ v^{corrected}_{dW^{[l]}} = \frac{v_{dW^{[l]}}}{1 - (\beta_1)^t} \\ s_{dW^{[l]}} = \beta_2 s_{dW^{[l]}} + (1 - \beta_2) (\frac{\partial \mathcal{J} }{\partial W^{[l]} })^2 \\ s^{corrected}_{dW^{[l]}} = \frac{s_{dW^{[l]}}}{1 - (\beta_1)^t} \\ W^{[l]} = W^{[l]} - \alpha \frac{v^{corrected}_{dW^{[l]}}}{\sqrt{s^{corrected}_{dW^{[l]}}} + \varepsilon} \end{cases}\]Where:

- \(t\) counts the number of steps taken of Adam

- L is the number of layers

- \(\beta_1\) and \(\beta_2\) are hyperparameters that control the two exponentially weighted averages.

- \(\varepsilon\) is a very small number to avoid dividing by zero often \(10^{-8}\)

Learning rate decay

Sometimes you need decrease the learning rate especially when you are about to reach convergence.

one way is:

\[\alpha = \frac{1}{1+decay-rate * epoch-num} \alpha_0\]Where

- \(\alpha_0 \): The initial learning rate.

- decay-rate is another hyperparamter you need to tune.

Other learning rate decay methods:

- \( \alpha = 0.95^{epoch-num} \alpha_0 \) (exponintially decay)

- \( \alpha = \frac{k}{\sqrt{epoch-num}} \alpha_0 \)

- And others ..

Notes:

- In linear algebra terms, m[:,n] is taking the nth column vector of the matrix m so taking the first 3 examples in input data X, X[:, 0 : 3]. (slicing). (important for programming assignment)

- Different optimization algorithms can leads to different accuracy so it’s important to always choose a good one.

- One epoch passes through all the \(m\) training examples whether you use batch, stochastic or mini-batch.

- Inside an epoch (iteration) you loop m times, 1 times or t times for stochastic, batch or mini-batches respectivaly.

- Very useful article: http://ruder.io/optimizing-gradient-descent/index.html

Resources: Deep Learning Specialization on Coursera, by Andrew Ng

Leave a Comment